Author: Professor Mehri Madarshahi

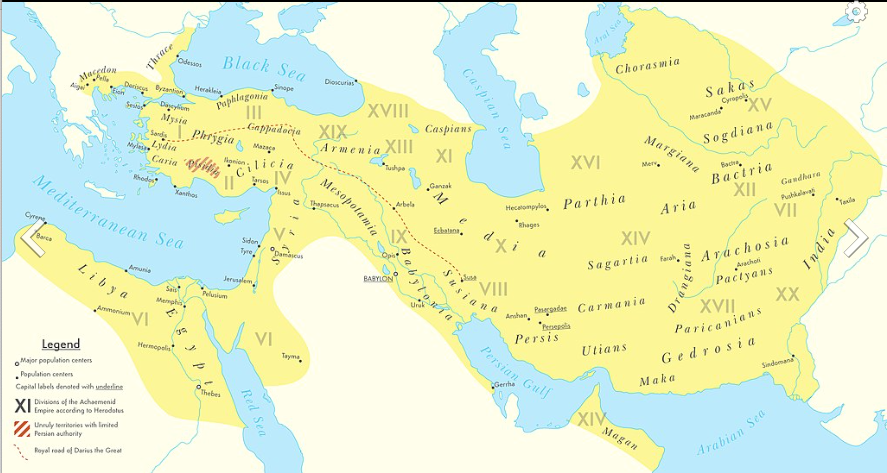

An ancient civilization of over 7000 years that stretched from northern and central ancient Greece, the Balkan and Eastern Europe in the West to the Indus valley in the East, the Persian Empire became known as the largest Empire in history. As one of the oldest continuously inhabited civilizations, Iran formed a bridge between the Semitic world and the Indo-Aryan civilization of South Asia. In its reduced present geographic location, Iran is still located at the crucial junction of South Asia and the Middle East and it links the Central Asian Republics and the Caucasus region to the Arabian Sea. Historically, it has continuously influenced its neighbors, irrespective of the type of government in power. Today, Iran ranks second in the world for natural gas reserves and fourth for proven crude oil reserves.

At present, despite crippling periodic sanctions imposed by the United States, Iran’s economy is slowly emerging from a decade-long stagnation. It has adopted a comprehensive strategy for continuous development in the context of its 20-year vision and its sixth development plan. The sixth plan comprises three pillars: the development of a resilient economy, progress in science and technology, and the promotion of cultural excellence. Among its priorities are the reform of state-owned enterprises and the financial and banking sectors, and the allocation and management of oil revenues. The plan envisions annual economic growth of 8%. Its GDP in 2020/21 was almost at the same level as 2010/11.

Iran at present

To survive the impact of the tough U.S. sanctions, Iran has strived to navigate ties between China and India, initially trying to maximize its benefits.

Given its important geopolitical location, Iran is being pulled in different directions by China, Russia, and India when it comes to their rivalry in economic and geopolitical spheres.

Nuclear Ordeal

Iran began developing its nuclear capability in the 1950s. In 1970 the country joined the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which granted the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) the right to monitor Iran’s nuclear programme. In 2002, when Western attention was fixed on Iraq, and an attack on Baghdad was imminent, information began to spread about Iran’s secret nuclear facilities in Arak and Natanz. It became clear that Iraq’s neighbour was moving at alarming speed towards a level of uranium enrichment that would permit making an atomic weapon. Based on an agreement with the US in 2003, Iran began to dismantle its nuclear facilities in exchange for lifting sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council. The deal fell through. Barack Obama, who had become US president in 2009, adopted the position that engaging Iran diplomatically was the only way to prevent a widespread conflict in the Middle East. This was the beginning of confidential American relations with Iran’s representatives in Muscat, the capital of Oman during Obama’s first term in the office. High-level negotiations with Iran involving the US, Russia, France, the UK, Germany and the European Union began in the autumn of 2013 in New York, leading to the meeting of interested parties to disable Iranian nuclear capability. Although it was a deja-vu but Iran – given the extreme uneasiness of the neighboring countries to the West – accepted to fully cooperate with the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, plus Germany and the EU to conclude a landmark diplomatic deal namely, the “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action”. The deal, the result of years of intense diplomacy, was signed in July 2015 and won the UN Security Council’s unanimous endorsement.

The Plan secured strict limits on Iran’s nuclear activities and the most extensive monitoring and inspection regime ever implemented by the International Atomic Energy Agency. In return, it also opened the prospect of lifting the economic ban imposed by the US, EU and the UN sanctions on Iran.

The full implementation of this deal was severely affected, however, by Donald Trump’s decision in 2018 who decided unilaterally to withdraw and to pursue a unilateral “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran. This decision came at the time that Iran was fully cooperating with parties and provided unimpeded access to IAEA for monitoring and inspection. In revenge, Iran heeding the call from opposition within its Government decided to ratchet up its nuclear activity and to limit IAEA monitoring. It failed to co-operate fully with the agency under the basic safeguards’ obligations.

New national elections in Summer of 2020 wiped out the moderate and pro-western government of Rouhani and replaced it with a hand-picked ultra conservative candidate, Raisi, chosen by the supreme leader Ali Khamenei who was from the beginning opposed to any deal with the West.

To return to the negotiation table, since 2021 and for nearly a year, EU-hosted talks in Vienna and against all odds brought Iran — now firmly under the thumb of hardline theocrats — closer to the US. President Joe Biden’s administration had pledged to rejoin the deal and lift many sanctions if Tehran falls back into compliance with the original accord. Iran demanded cast-iron assurances that no future US administration would pull out again, the lifting of all Trump’s sanctions and the delisting of the Quds army and the Grand Ayatollah’s name from terrorist lists established by the US.

In November 2021, Western officials were pressuring Iran to agree to a deal within days, arguing that if it would not, the moribund accord would be redundant because of the advances Tehran had made with its nuclear programme. The three European signatories issued a joint statement calling “on all sides to make the decisions necessary to close this deal soonest”. In February 2022, Tehran and the global powers were nearing an agreement to revive the 2015 nuclear agreement that would lead to Iran radically reversing its nuclear programme in return for the US rejoining the accord and lifting many sanctions imposed on the country. However, an unexpected demand from the Russian Federation – one of the signatories to the agreement – calling for guarantees that US sanctions on Russia since March 2022, would not impede its trade with Iran. The Russian news agency reflected Moscow’s demand stating that: “We need guarantees that these sanctions won’t affect the regime of trade-economic and investment ties with Iran”.

Under the JCPA agreement, excluding Russia would be difficult as Iran was to transfer its enriched uranium and heavy water to Russia. However, on 15 March 2022, Russia withdrew its demand for a wider exemption, partly in response to Iranian diplomatic efforts.

One of the major considerations for these negotiations and lifting the embargo on Tehran selling its oil freely was that it could add crude supply of more than 2mn barrels a day to the world stockpiles alleviating partly the new oil shock, exacerbated by US moves to ban Russian oil imports, and a “buyers strike” by companies wary of reputational damage if they buy oil from Russia now.

Failing to persuade its traditional ally, Saudi Arabia, to start pumping its spare capacity, the US tried to open lines to Venezuela, another sanctioned oil producer. Despite the havoc created by shortage of crude oil and gas in the world, Opec is still sticking to the production limits it has set in partnership with Russia.

The last stretch of the negotiations with Iran coincided with the war in Ukraine and the subsequent significant economic and financial sanctions imposed by the west on Russia – a signatory to the accord and an important player in the EU-mediated Iran talks in Vienna – leading to a hardening of positions by all parties to the negotiations.

These tactical delays may embody a greater risk for either the US or Israel taking pre-emptive action to launch attacks against Iran’s nuclear facilities. American commanders have already warned that the US has a robust range of military options to deter Iran. Israel has ordered its military to prepare for potential strikes against the country.

As one of the last-ditch efforts, in early July 2022, President Biden travelled to the Middle East and met with Israeli and Arab Rulers. In one of his statements, in relation to the on-going meetings with Iran on nuclear negotiations, Biden mentioned that “Should diplomacy fail, the US and its allies are considering options such as to seek a resolution to censor Iran at the next governor’s board meeting of the IAEA, scheduled for March. That would then go to the UN Security Council, which would determine what action to take”.

In the wake of Biden’s trip to the region, Putin visited Iran. He attended a summit of the “Astana Process” and held separate talks with his Turkish and Iranian counterparts. The meeting was an opportunity for Moscow to send several important signals to the powers of the Middle East. At a bilateral meeting with the Iranian President, bilateral economic cooperation, and the preparation of a new strategic agreement between Moscow and Tehran were discussed. Putin stressed Moscow’s desire to strengthen the relationship with Tehran, whose strategic importance has increased since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine.

In the long run, Russia also aims at strengthening the China-Iran-Syria geopolitical network, to which it would be tempted to include India. BRICS may serve this foreign policy aimed at building an alternative international order to that dominated by the United States and its Western allies. During the 19 July 2022 meeting, Moscow and Tehran clearly wanted to show that a new geopolitical reality is taking place and that the West now has less power and influence than it did ten years ago. This is a real challenge for the United States and the European Union, which will have to adapt their foreign policies, their doctrines, and the choice of their instruments, so as not to be overtaken on the international chessboard.

Apart from Russia, Iran has become increasingly friendly with China and is willing to do what China asks without violating Russian pride. Iran

a) is a participant in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative.

b) partners with China in the oil fields;

c) participates in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), with the SCO members having already approved in September 2021, the launch of the procedure for Iran’s entry into the organization;

d) has now engaged China as its largest trading partner, investor, technology provider, providing a huge market for Iran.

The giant Iran has the capability and pool of intellectual talents and advanced military and naval programmes.

.

Geopolitical challenges

Concerns for Iran’s reach in the Middle East do not only relate to its nuclear programme but Its political, military and financial influences in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Lebanon (see map below).

Iran strategic penetrations in Western Asia

Taking advantage of the regional instability and the weak state of Lebanon Iran has maintained since 1980 a separate army in Lebanon. It is integrated into the Lebanese political system and society through Hezbollah’s political representation and provision of social services and education.

As a counterbalance to Hezbollah, foreign actors, including the US, UK, and France, have provided support to the Lebanese military and the Israeli army and political strata are fully engaged in the Lebanese theatre.

In Iraq, Iran from 2003 and since 2010 has provided financial support and trained a militia army active in the politics of the country. In its engagements Iran is facing serious challenges from the US, Britain, Israel, and Arab countries.

In Yemen by providing finance and training to Houthis (the militia groups) Iran has blocked the influence of the Saudi-led Government in the country since 2014.

Alongside Russia, Iran has been a significant backer of the Assad government in Syria since 2011. With the two countries being long-standing allies, Iran has supported the Syrian Government with military and financial aid.

The Arab Gulf States – such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – consider Iran’s actions to ferment “sectarian strife” in Bahrain of great concern and have repeatedly requested that Iran stop backing Bahraini opposition groups.

The International Crisis Group has cited several reasons for Iran’s geopolitical strategy in Western Asia and beyond. These include: ·

To seek security of the regime through a “forward defence” strategy, meaning it battles its enemies in other states (e.g., Lebanon, Iraq).

·To act to protect Shia Muslims. Iran is a Shia-Muslim majority state, while most regimes in the Middle East are governed by Sunni Muslim rulers—notably Saudi Arabia.

·To combat the US, Israel and other competitors such as Saudi Arabia to maintain its established status quo.

·To spread a wide-spectrum economic and financial influence through bi-lateral alliances with various countries such as Brazil, Venezuela and Argentina and others in Latin America.

In 1984, the US designated Iran as a “state sponsor” of terrorism – one of only four countries to be on the list. The US argues that Iran’s actions create instability in the region, and its use of proxies and local militia groups provide deniability “in an attempt to shield it from accountability”.

A UN arms embargo against Iran expired in 2020 which was planned to take place five years after the JCPOA was signed by all parties. The UK expressed concern at the decision, but so far no consensus could be agreed to renew it.

Iran a giant naval power-Caspian Summit

Historically, Russia as a northern neighbor has become entangled with Persia/Iran leading to the development of complicated political, economic, and social linkages. The recent discord with the West has enhanced the necessity of further and deeper relations with Iran which is being considered a point of salvage from the sanctions imposed upon Moscow by the West. As a result, Moscow is keen to revive the North-South naval corridor through the Caspian Sea.

Four years ago, after 22 years of talks, the five Caspian littoral states -Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Iran – were to sign an agreement on the delimitation of the surface area of the sea and agreed to exclude the military forces of all non-littoral states from the area. In the intervening years, four of these countries have ratified the accord; but one – Iran – has not. The reasons for this lie in both the complicated history of the new delimitation of the Caspian after the Soviet Union’s demise and Iran’s expanded military presence there.

Tehran’s refusal to ratify the accord rests not only on the issue that it did not acquire a large enough portion of the Caspian Sea but also on the fact that the 2018 accord did not resolve serious issues related to the delimitation of the seabed and how dividing lines should be drawn from border points between neighboring countries. International law would leave Iran in control of a larger seabed with plentiful oil and gas reserves. The seriousness of these unresolved issues was reflected in the difficulties Baku and Ashgabat faced in working out their disagreement about demarcation lines in a disputed Caspian gas field (Stan Radar, January 22). Tehran’s disagreement with the existing arrangements is becoming an increasingly serious problem. The Sixth Caspian Summit publicly recorded a strong discord by Iran preventing it from reaching a comprehensive agreement on the opening of this traditional East-West route narrowing the hope for Russia significantly. If Moscow is going to make any progress on a new trade corridor, it will have to make new concessions to Iran that would likely trigger objections from the other parties. Russia could rely exclusively on land routes, which would leave the north-south corridor less effective or continue to make plans in hopes that Iran will not challenge current arrangements.

In the run-up to the June 2022 Caspian Summit in Turkmenistan, Moscow had expected that Tehran, animated by the same anti-Western sentiments as Russia, would cooperate closely in the opening of a north-south transport route between Russia and the Indian Ocean. This plan would have allowed Russia to effectively circumvent Western sanctions. Yet, as continuing disagreements between Iran and the other Caspian littoral states were highlighted at the meeting, Moscow has not succeeded in its overtures. Moscow continues pressing Tehran hard on this point, recognizing that, without Iran’s ratification, it will be difficult to reach accords on many other related issues (Casp-geo.ru, July 6; Nezavisimaya gazeta, June 30)..

Reaching an agreement on such issues has been further complicated by the expansion of the Iranian naval presence in the Caspian. This has not only challenged the traditional dominance of Russia’s Caspian Flotilla but has also raised questions about whether Tehran may challenge Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan in the sea.

Until recently, Iran’s naval presence on the Caspian was too small to challenge Azerbaijan or Turkmenistan, let alone Russia. But shortly after the Ashgabat summit concluded, Tehran held a new exercise to signal that the situation is changing, pointedly declaring it now has the capacity to act on its own in the Caspian and listing a far larger inventory of forces than ever before, including “various surface and flying units of the navy, including missile launchers, sea-based helicopters and UAVs, as well as electronic warfare systems” (Iran Press News Agency, July 8). Iran maintains what is estimated to be the “largest ballistic and cruise missile force in the Middle East.” Some of its missiles are capable of striking targets 2,500 kilometers from Iran (reaching Israel, the Balkan and northeast Africa).

Coming on the heels of Tehran’s reiteration of its refusal to ratify the 2018 accord, Moscow may now face even larger problems in the Caspian region that raises questions about the potential opening of a new transport corridor. The reaction of Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Turkey to Iran’s recent moves points to a possible naval competition that could easily spark a new struggle for power on the Caspian – a struggle that Russia would inevitably be drawn into. For now, all Russian hopes are invested in the upcoming Second Caspian Economic Forum negotiations which is rescheduled for October 2022 in Russia. The first such event took place in 2019 in Turkmenistan.

The main objective of this meeting is to reach an Agreement between the governments of the Caspian states on trade and economic cooperation as signed at the Fifth Caspian Summit in Aktau. The agreement was to further strengthen and develop interaction between the coastal states in industrial, trade, energy, transport and logistics, innovation, tourism, information, and other areas of interest.

Dimitry Medvedev as the then chairman of the government of the Russian Federation stated that “the holding of this international conference would contribute to the expansion of cooperation between the Caspian states in all areas – from ecology to education”. He further added that “it is important to continue the implementation of measures to develop cooperation in the transport sector, to reach new agreements that will increase the volume of trade turnover of regional states through the created transport infrastructure”. During the Second Caspian Economic Forum, a regular meeting of the Assembly of State Universities of the Caspian States will be held, within which universities can reach new agreements, namely, to strengthen scientific ties in the region. Joint scientific projects in the field of economy may contribute to the development of trade and economic cooperation in the region.

The Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea has not yet entered into force. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov expressed hope that the Iranian parliament would soon ratify the convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea.

Therefore, as is, it is difficult to predict when this all-important issue and that of nuclear accord will be finally resolved. Maybe other crisis such as the one recently in the relations between Baku and Tehran will eventually incite Iranian parliamentarians to assess the provisions of the Convention and the principles of the parties’ activities more favorably in the Caspian as stipulated by the agreement.